Delville Wood Read online

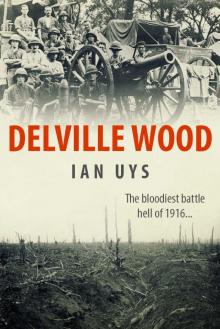

DELVILLE WOOD

July 1916

IAN UYS

Copyright © Ian Uys 1983

The right of Ian Uys to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

First published in 1983 by Uys Publishers.

This edition published in 2018 by Endeavour Media Ltd.

Devil’s Wood

“No battlefield on all the Western Front was more bitterly contested than was “Devil’s Wood”, where fighting, practically uninterrupted and intense, went on for six consecutive weeks from mid July till August 26 of 1916. It was in the first week of the struggle that the South African forces won their imperishable fame — grimly hanging on against overwhelming odds and repulsing counter-attacks by troops five and six times their number.”

(The Times, London, 1917)

The bloodiest battle hell of 1916

“… In the depths of Delville Wood, during the ensuing days, the South Africans made their supreme sacrifice of the war — where today a white stone collonade of peaceful beauty commemorates, and contrasts with, the bloodiest battle hell of 1916.”

(Sir Basil Liddell Hart in History of the First World War)

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1 — The First South African Infantry Brigade

Chapter 2 — Flanders and the Somme

Chapter 3 — Bernafay Wood and Trones Wood

Chapter 4 — Longueval village

Chapter 5 — Taking the wood

Chapter 6 — In-fighting

Chapter 7 — Holding on

Chapter 8 — The bombardment

Chapter 9 — The Bitter-enders

Chapter 10 — Relieved

Chapter 11 — Aftermath

Chapter 12 — Memorials

Biographies

Roll of Honour 14-20 July 1916

Nominal Roll of Infantry Officers at the Somme in July 1916

Delville Wood Decorations

Recommendations for mentions in despatches

Bibliography and sources

Abbreviations

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to many people for assistance in research for this book. It would be difficult to thank all personally, however I wish especially to acknowledge my gratitude to the veterans of Delville Wood and their relatives who assisted me so willingly.

To all publishers of the books listed in my bibliography for which I have quoted extracts, my sincere thanks. In addition I appreciate the assistance, encouragement and help of the following:

Commander Mac Bisset of the Military and Maritime Museum at Cape Town;

Miss Fiona Barbour of the McGregor Museum, Kimberley;

Colonel George Duxbury and his staff at the SA National Museum of Military History;

Colonel Albert Cilliers MC, of the SA Agency of the Commonwealth War Graves Board;

Miss Rose Coombs of the Imperial War Museum;

Mr Peter Digby, the honorary curator of the Transvaal Scottish Regimental Museum;

Mr Don Forsyth for bravery citations;

Mr and Mrs Tom Fairgrieves of Delville Wood Cottage, Longueval, France;

Mr Dennis Gee for interviewing survivors in the border area;

Major Annette van Jaarsveld of the Army Documentation Services;

Mr Nick Kinsey for valued and timely advice;

Messrs Henry Holloway and Ivan Scholtz; and

Mrs Ursula Abdinor (nee Strohmaier) for translations.

Foreword

I regard it as an honour that I should have been invited by the author of this publication to contribute a foreword thereto.

The personal experiences of some of the survivors of the battle of Delville Wood have already appeared in print as a result of overseas writers asking them to furnish written particulars, but I think Mr Uys is the first South African to have undertaken the task by means of personal interviews.

I myself have been unable to offer much contribution to this collection, as I was the victim of shell fire and was carried out before my unit had even reached the wood, but the descriptions which Mr Uys has gone to so much trouble to collect are of particular interest to me, some having been obtained from survivors whom I personally knew. Regrettably most are no longer with us.

The story of Delville Wood has oft been told, originally by John Buchan in his The South African Forces in France, now long out of print. Many subsequent publications have recorded the factual story of the event, but the personal touch which Mr Uys has been able to offer presents a fresh light and makes fascinating reading.

I wish him all success in his undertaking.

A W Liefeldt.

Chairman, Cape Town Branch.

SA Overseas Brigade Association.

Introduction

The Battle of the Somme marked a turning point in warfare. Beforehand cavalry was the supreme weapon, afterwards the tank and aircraft reigned. Cavalry was used at the beginning of the Delville Wood fight and tanks at the conclusion in September 1916. For a brief spell it was the war of the infantryman alone. At Delville Wood the 1st South African Infantry Brigade was to show what that meant. Their feat can never be surpassed.

Delville Wood is commemorated in South Africa by an annual service. Yet ironically no South African military unit carries it as a battle honour on a regimental colour. In addition, though it is generally known as the bloodiest battle ever fought by South Africans, very little is known of the men who were there.

On 14 July, 121 officers and 3,052 other ranks comprised the 1st South African Infantry Brigade. Six days later Col Edward Thackeray marched out with two wounded officers and 140 other ranks. Of these survivors one officer and 59 men of the light trench mortar battery had joined as reinforcements two days earlier.

The bare statistics of the battle have sufficed for too long. In these pages we learn of the men who came out of the hell of “Devil’s Wood” and of the men who didn’t. Some years ago I was shown a booklet in which a grieving father recorded his tribute to his son — one of the South Africans who still lie in the wood. “It is very hard to part with him, but I glory in his glorious end, my splendid, chivalrous boy …”

The South Africans, both English and Dutch speaking, took and held the wood. For six days and five nights they fought and died in an inferno of exploding shells, flame-throwers, machine-gun and rifle fire. The shelling which reached seven shells a second reduced the wood to a wasteland.

The Springboks hurled back overwhelming attacks by masses of enemy infantry until overrun and virtually destroyed. They fought hand-to-hand with the best troops in the German army.

Outnumbered and attacked from three sides, their orders were to hold the wood and they did so. Colonel Thackeray inspired the bone-weary men by his example. He fought as a private would, with rifle and Mills bombs. When the survivors eventually paraded before Gen Lukin he took the salute with tears in his eyes.

Why should Delville Wood be commemorated when other battles are not? In answer John Buchan wrote, “There were positions as difficult, but they were not held so long; there were cases of as protracted a defence, but the assault was not so violent and continuous … As a feat of human daring and fortitude the fight is worthy of eternal remembrance by South Africa and Britain, but no historian’s pen can give that memory the sharp outline and the glowing colour which it deserves. Only the sight of the place in the midst of the battle — that corner of splinters and churned earth and tortured humanity — could reveal the full epic of Delville Wood”.

Bearing this in mind, I have borrowed liberally from accounts given by the men who were there and in this resp

ect it is their book. Accordingly I make no apology for the large number of quotations used. Publishers’ names are given only for books not mentioned in the bibliography.

An overall picture is presented of each day’s fighting. The official accounts of the brigade, attached units and the four regiments follow. The experiences of the individuals involved are recorded within these units and listed in company order. It is thus possible to follow any one man’s reminiscences by referring to his company in each chapter.

As far as possible the day-to-day events have been recorded by company for ease of reference. Where the company is not known the relevant text is included with that of the battalion headquarters. Imperial measures, units and ranks are recorded as they were at the time.

In addition the Battles of Bernafay Wood and Trones Wood are included, as they preceded Delville Wood and the latter should not be seen in isolation.

The brigade was to endure much in the remaining years of the Great War — and many Delville Wood veterans were yet to pay the supreme sacrifice. I am grateful to the veterans of this epic battle who have assisted me in compiling this book. It is to them and their departed comrades that this book is dedicated.

Chapter 1 — The First South African Infantry Brigade

In common with other epic events the story of Delville Wood had humble beginnings — the dry, dusty parade ground at Potchefstroom, Transvaal. A scene far removed from the cool, green woods and rolling grass covered hills of the Somme in France — the last scene that many South Africans would see.

The August winds of 1914 whipped up the powdery surface to coat the marching recruits with dirt. Their sweat ran it in rivulets from faces and necks into tunic collars. Though the men muttered and cursed under their breaths, their vigilant officers knew the value of well-disciplined, hardened troops — and the parade ground was the first step in shaping the brigade.

Most of the volunteers had served through the arduous German South West African Campaign and had participated in forced marches under the searing desert sun. Their overriding desire was to serve in France and many feared that the war would end before they saw the poppies of Flanders.

The prime minister, Gen Louis Botha, had personally commanded the Union troops in SWA, with Gen Jan Smuts as his second-in-command. The decision to form the brigade for overseas service had been theirs — a decision which would radically alter the lives of thousands of men.

The Union Government’s offer to send a contingent of South African soldiers to fight in Europe was accepted by the Imperial Government in July 1915. The War Office specifically requested an infantry unit, which meant that it had less attraction for the Afrikaners who had proved themselves superb light cavalrymen during the South African War and the German SWA campaign. Thus only about 15% of the original brigade comprised South Africans of Dutch extraction.

In view of the small white population it was decided that a brigade would be all that South Africa could raise. It would comprise four battalions representing the main divisions of the Union. The 1st South African Infantry Battalion was from the Cape Province, the 2nd SAI from Natal, the Border (Kaffrarian Rifles) and the Orange Free State, the 3rd SAI from the Transvaal and Rhodesia and the 4th SAI was drawn from various SA Scottish regiments in South Africa.

There were few if any brigades in the world with a better class of men. The level of education and breeding of these “colonials” was very high. Most had previous military experience in territorial, volunteer and irregular units and some had served in the regular army. The middle-class men who volunteered for service overseas were those who fought because they had much to fight for.

*

Brigadier-General H T Lukin CMG DSO, was appointed to command the brigade. Henry Timson Lukin, 55, was the Inspector-General of the Union Forces. Born in Fulham, England, in 1860, his ambition and family tradition pointed to a military career. He sailed for South Africa to serve in the Zulu War of 1879, was commissioned in Bengough’s Horse, and was seriously wounded during the Battle of Ulundi.

Lukin served with the Cape Mounted Riflemen in the Basutoland Campaign of 1881. In 1891 he married Lily Quinn while stationed with the CMR in Alice. Two years later he was sent to England to attend courses in gunnery and military signalling. On his return to South Africa in 1894 Lukin was promoted to captain. He commanded the CMR Artillery troop and was also the signalling instructor. During the Langeberg Campaign of 1896-7 he commanded the Maxim-guns and signalling staff and served as field-adjutant of the Bechuanaland Field Force, being often mentioned in despatches.

During the South African War Lukin commanded the CMR Artillery at the Siege of Wepener, for which he was awarded the DSO. Thereafter he led a mounted column in the Cape before taking command of the 1st Colonial Division in the Cape (CMG 1902). He was granted the honorary rank of lieutenant-colonel in the Imperial Army in recognition of his service during the war.

In 1903 Lukin was promoted to colonel, commanding the CMR, a regiment which he said in later years he was extremely proud to command. In June the following year he was also promoted to the rank of commandant-general of the Cape Colonial Forces.

In May 1911 Lukin proceeded to England in command of the contingent of the Union of South Africa at the Coronation of King George V. He then travelled to Switzerland to study the Swiss Military system, before returning to South Africa in January 1912.

When the SA Defence Act of 1912 was passed Lukin was appointed Inspector-General of the Permanent Force of the Union Defence Forces, with the rank of brigadier-general.

When the First World War began he commanded the SA Mounted Riflemen Column and subsequently the SAMR Brigade in German SWA between September 1914 and July 1915. After Gen Botha’s departure Lukin took over command of the Union Forces in SWA. Despite his arduous life of campaigning he retained his inherent humanity and was a respected and much loved commander.

*

Volunteers were encouraged to join the battalion of their choice, which generally represented their province. The political situation was still unsettled following the suppression of the Rebellion by the Union Defence Force. To send the Permanent Force to Europe would not be wise, especially as it became obvious that South Africa would have to assist in the East African Campaign. The brigade would thus consist only of volunteers and would fight in the British Army and be paid at the rate applicable to British regular soldiers.

The brigade assembled at its depot at Potchefstroom, where there were facilities for mobilisation. Major James Mitchell-Baker of the UDF General Staff was appointed as brigade-major, Captain Arthur Pepper as staff captain and Lieut-Col P G Stock as senior medical officer.

James Mitchell-Baker, 36, had left his law studies in Glasgow in 1895 to join the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and came with them as a lance-corporal to serve in the South African War. In March 1901 he joined the Scottish Horse for the duration of the war and resigned his commission in the British Army in July 1902.

In 1908 Baker resigned from the army and went to Pretoria. He represented South Africa at the Olympic Games in London that year, taking part in the marathon. He was appointed as a second-lieutenant in the Transvaal Scottish Volunteers in 1909 and was promoted to lieutenant the following year. In 1912 at the request of Gen Smuts he rejoined the Permanent Force with the rank of captain and became the first staff officer of the Union Defence Force.

Baker was promoted to major in 1914 and accompanied Gen Botha to SWA where he was acting chief staff officer to the Northern Force. He was recalled to Defence Headquarters as staff officer for general staff duties, then in August 1915 appointed brigade-major to the 1st SA Infantry Brigade.

General Lukin’s choice of the four battalion commanders was significant. In the Somme offensive one was to be killed, one badly wounded, one recommended for the Victoria Cross and the other would survive to command the brigade in its greatest defeat, when he would be taken prisoner.

*

The Cape of Good Hope Battalion’s commanding officer

, Lieut-Col F S Dawson had recently commanded the 4th South African Mounted Rifles. Frederick Stuart Dawson, 40, was born at Brighton, England in 1873. He was commissioned in the 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers and served in India and Malaya from 1893 to 1897.

In October 1896 Dawson married Miss R Hewitt who died shortly after. He came to South Africa to serve in Robert’s Horse in January 1900. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the SA Constabulary a year later and promoted to captain in July 1901 and was mentioned in despatches.

In 1908 Dawson was transferred to be Inspector of the Orange River Colony Police. In April 1910 he married Miss Eileen Braby at Bloemfontein. Three years later Dawson was promoted to lieutenant-colonel of the SA Mounted Riflemen and during the SWA Campaign he commanded the 4th SAMR. The Cape Battalion’s four companies were:

A Company (Representative of Western Province; Commanded by Capt P J Jowett)

B Company (Eastern Province; Capt G J Miller)

C Company (Kimberley (Workers); Capt H H Jenkins)

D Company (Cape Town (Clerical); Major E T Burges)

*

The Natal and OFS Battalion was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel W E C Tanner, the district staff officer of Pietermaritzburg. William Ernest Collins Tanner, 40, was born at Fort Jackson, Cape, in 1875. He was educated at Hilton College, Natal, then in 1893 joined the Natal Carbineers. Four years later he represented the Carbineers in the Natal Militia Contingent at Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations.

During the South African War he took part in the Defence of Ladysmith, then served with the Scottish Horse in the Transvaal and on the Zululand frontier. At the conclusion of hostilities he transferred to the Natal Militia Staff.

Captain Tanner fought against the Zulus in the 1906 Bambata Rebellion. In 1909 he married Isobel Erskine at Pietermaritzburg and they had two sons, Erskine and Brian. During 1909-10 he attended the Royal Staff College at Camberley, England, and graduated psc (passed staff college). Tanner then transferred to the Union Defence Force with the rank of major.

Delville Wood

Delville Wood